Business Model Illustration of Academic Journal Publishing and a Discussion of the Causes

Introduction

I’m an independent researcher interested in research automation. In this article, I would like to illustrate the business model of academic journal publishing. I hope to convey what people think is problematic about academic journal publishing. In the latter half of the article, I will discuss why this business model is established in the first place.

I am neither an expert on academic journal publishing nor a business expert, so I might have misunderstood some things. If anyone notices anything wrong, I would appreciate it if you could point it out to me!

What is business model illustration?

The business model illustration is a method of visually explaining business models proposed by Charlie, CEO of the Japanese think tank Zukai Soken. I did the business model illustration of academic journal publishing using the free illustration toolkit he distributes (in Japanese).

Business model illustration of academic journal publishing

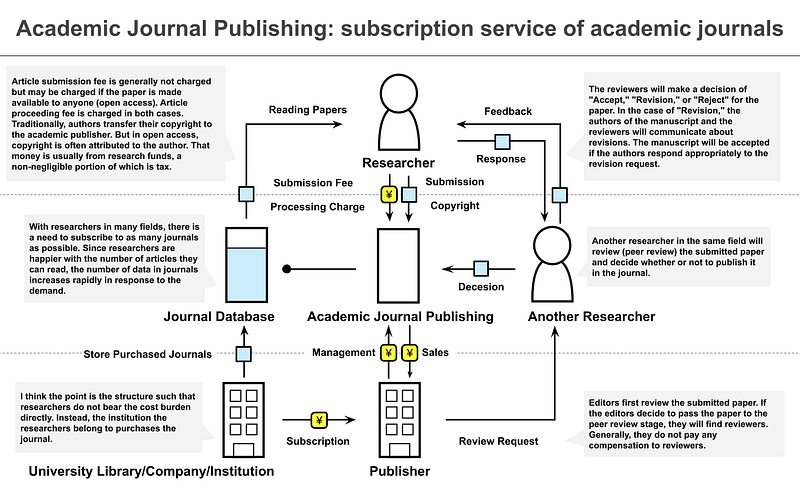

Explaining the illustrated business model

Here are the results of the business model illustration. The top corresponds to users, the middle to businesses, and the bottom to operators. Light blue represents the flow of information and yellow represents the flow of money. I will explain this business model below.

The business model of academic publishing is quite simple. The publisher simply publishes articles submitted by researchers in journals and makes money from the subscription fees. This alone is not much different from the ordinal journal publishing business, so there seems no need to illustrate it.

However, academic publishing has several characteristics unique to the research industry. In preparation for explaining them, we will first explain how articles are published and delivered to researchers.

Paper publication steps

First, when a researcher writes a research paper, they submit it to a publisher. Editors first read the submitted paper, judging whether it is in line with the theme and objectives of the journal.

If the paper passes this review, it will go to the peer review stage. Peer review is a process in which researchers who are experts in the same field of research papers review the paper. Research papers are documents with extremely highly specialized content. Therefore, a non-specialist can’t judge whether the claims made in the paper are valid and whether the content is academically valuable. This is why other researchers must determine whether or not the paper can be published in the journal.

Reviewers make a decision as a result of the peer review process: “Accept,” “Revision,” or “Reject. If “Revision,” the author(s) of the paper will address the items that require revision. This can range in degree from a slight change in wording to additional experimentation. It can take several months or even years. Once accepted, the paper is edited by the publisher and is finally published.

In most cases, researchers do not subscribe to academic journals directly. Instead, the institution to which researchers belong subscribes to them. In particular, in the case of researchers in a university, the university library subscribes to journals. The library adds subscribed journals to the university’s journal database, and researchers read the submitted articles through the database.

Peculiarities of academic publishing

We have described the general flow of academic publishing. At first glance, this is an ordinary publishing business. However, there are a number of distortions in this business structure.

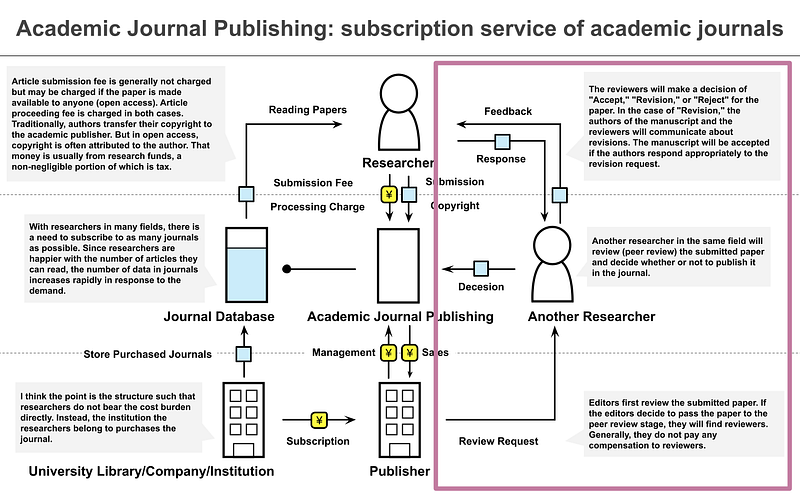

The first is that publishers do not pay for reviewers. Peer review is an important part of the work that determines whether an article is accepted for publication. However, it is generally done on a volunteer basis. As mentioned above, reviewers not only examine papers but also provide feedback on them. These are all for free. Furthermore, reviewers’ names are not made public. Therefore, others do not know how much the reviewers have contributed to the review of a paper. Current reviewers review purely for internal rewards.

Second, publishers do not pay researchers. Publishers make money by selling the journals in which the papers are published. However, the authors of the research papers are not paid. On the contrary, the author pays the article proceeding fee when their manuscript is accepted for publication.

In recent years, open access has become popular, which allows authors to read articles without subscribing to a journal. In this case, authors may also pay an article submission fee when submitting their paper. This is to compensate the publishers for the profit they would have earned from the sale of the journal.

Third, authors transfer their copyright to the publisher. In the case of open access, copyright often belongs to the author. Traditionally, however, copyright belongs to the publisher of the journal. Therefore, it is a violation of copyright to display one’s own paper on a website without permission (this is often allowed as an exceptional case, though).

One major problem with this is that much of the research is supported by public funds, i.e., taxes. In other words, taxpayer-funded research has become the work of a private company, and unless you pay for it, you cannot even read it. This situation is sometimes referred to as an article held back by a paywall.

Profit structure of academic publishing

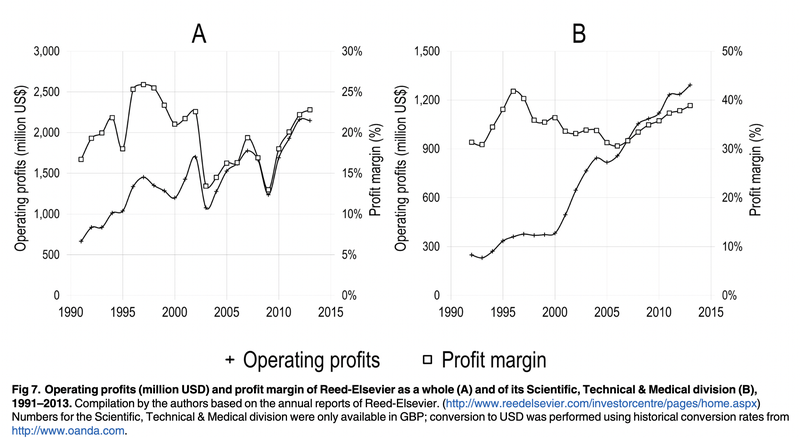

As you may have noticed from the business model illustration and the explanation, very little money is leaving the publisher. Of course, operations, including editing, etc., are hard work, but more money flows into the publisher.

In fact, major publishers have consistently made profit margins of 30~40% in recent years. Below is a chart of profit margins for the well-known RELX Group (formerly Reed Elsevier) through 2015. It can be seen that profit margins have grown rapidly, especially in the science and technology sector (including academic publishing) since the 2000s (Figure B).

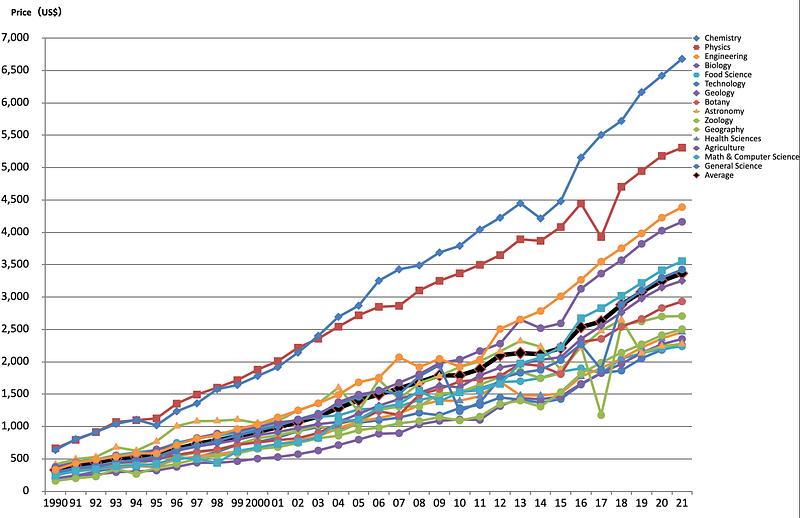

A look at the average price of natural science journals by field shows that prices have increased more than fivefold over the past 30 years. In some cases, prices have risen nearly tenfold. These rising prices are putting pressure on the university’s finances.

Introduction to the later half

When did academic publishing become this business model? And why does this situation still exist today? In the second half of this article, I will explain these questions.

I have referred to two Japanese sources for this explanation. The first is a book by Dr. Masaki Arita of the National Institute of Genetics titled “The Road of Academic Publishing.” As the title suggests, it is an excellent book describing how academic publishing was born and how it has become what it is today.

The second is a document entitled “The History of Academic Journal” written by Ryota Yamada, CEO of fuku Corporation. It is very informative to learn the history of academic publishing compactly with slides.

When did the commercialization of academic journal publishing begin?

So-called scholarly publishing is said to have begun in the 17th century. However, from the 17th to the 19th century, many academic journals were not as profitable as they are today, and many publishers struggled to stay afloat.

A businessman Robert Maxwell and the publishing company he founded in 1951, Pergamon, changed academic publishing into the business model we know today. Since his arrival, academic journal publishing has become rapidly commercialized.

Robert Maxwell - WikipediaIan Robert Maxwell (born Ján Ludvík Hyman Binyamin Hoch; 10 June 1923 - 5 November 1991) was a Czechoslovak-born…en.wikipedia.org

Why did the commercialization of academic journal publishing begin?

Maxwell’s business style

I believe that the reason for the commercialization of academic publishing can be summed up in one word: Maxwell did business well.

The publishing style of Maxwell was quite simple: publish new journals one after another. But it was perfectly suited to the needs of researchers.

Journals are a place for researchers to present their work. Therefore, researchers were grateful that more diverse journals appeared and accepted more papers quickly.

For example, computer science, molecular biology, and brain science were unorthodox fields at that time. This made it difficult to publish these works in traditional journals. Maxwell approached researchers in these fusion fields and appointed them editors to publish papers in new fusion fields. In addition, the publication cycle of academic conferences was too slow for researchers. Researchers wanted to report their results before the competitor and to make their achievements quickly to get a job. Maxwell responded to this need by creating journals with a fast publication cycle.

Maxwell entertained and incorporated researchers in various ways to publish new journals. He attended many conferences and held parties, invited researchers to his villa, took them out on his yacht, gave them checks, and gave them airplanes (!?). Such hospitality was a powerful magnet for researchers who had been far away from the glamorous world. In particular, the hospitality extended to mid-career researchers. Combined with the publication of the new journals, Maxwell must have been a truly wonderful person for the researchers of the time.

As a result of publishing more and more journals in this way, Pergamon went from publishing 40 journals in 1959 to as many as 150 in just six years. As a result of this expansion, university libraries had to purchase an enormous number of journals. This put pressure on the cost of the university library, which I mentioned above.

Factors behind Pergamon’s breakthrough

I explained that Pergamon increased its number of publications because of Maxwell’s business strength and because the journal served as a place to evaluate performance. But that was not the only thing that solidified Pergamon’s position in commercial publishing.

First and foremost, journals have a “competitors do not compete with each other for profits” nature. An article is a report on what has been revealed for the first time in the world. By their very nature, no two studies are the same. Therefore, if the paper you want to read is only available in a journal, you will be forced to buy that journal.

Because of this nature, as new papers and new journals appear, university libraries must purchase them continuously as long as researchers need them. This is why the more journals you produce, the more money you can make.

Further fueling this trend was the emphasis on basic science in the 1960s, when, Western countries invested huge amounts of money in science in response to the Sputnik Crisis. This resulted in instituting several policies to subsidize scientific research. This allowed academic journal publishers to reduce their burden and increase their revenues.

Sputnik crisis - WikipediaThe Sputnik crisis was a period of public fear and anxiety in Western nations about the perceived technological gap…en.wikipedia.org

And this science-focused policy ultimately led to high subscription fees for academic journals. The high profits of this period became the benchmark for academic journal publishing. Even after the scientific boom, it compensated by raising subscription fees (already in 1988, Pergamon’s profit margin was 47%).

Dr. Masaki Arita, author of “The Road of Academic Publishing,” accurately points out where the problem lies as follows.

The increase in journal prices is due to the demand for publication by researchers. As research funding declines, competition among researchers increases and the demand for publication increases. As the number of submissions increases, publishers will either increase the number of pages or launch new journals in proportion to the increase. In any case, they will not move in the direction of reducing profit margins, which were originally set high.

Pergamon was acquired by Elsevier in 1991. Three years later, Elsevier raised its subscription fees by 50% (!?). Nevertheless, for the reasons discussed above, university libraries could not stop subscribing to the journal. The reins have been completely taken over by commercial publishing.

Another major factor that supported this profit structure was the fact that researchers originally did the work of academic journal publishing on a volunteer basis. Since they did also peer review on a volunteer basis, there was no resistance among researchers to continuing to do peer review for free.

Rather, the publishers took over all the editing, coordination, bookbinding, and other work that researchers had been doing themselves. Instead, they only had to take care of the truly scholarly discussions. It must be a blessing for researchers at the time.

The style of publishing that Maxwell established was simple. But this was the decisive move to exploit great wealth from the research industry.

Why is the problem of academic journal publishing not resolved yet?

I have explained that the academic journal publishing business has a distorted structure and that this was a consequence of the commercialization that began in the 1950s.

In fact, in the 1980s, university books already raised the issue of high-profit margins in academic journal publishing. Why, then, has this problem not been resolved to date?

Journal rankings gain authority

The first question is, “Why did the journal continue to be the place to publish achievements?” If it is a problem that journals are the place to announce our achievements, why don’t we move to a different place to present our achievements? However, the authority academic journal ranking gained made this practically infeasible.

The academic journal ranking began to gain authority since the appearance of Cell in 1970. Cell is still the top journal in life science today. It started as a journal that published only research reporting epoch-making results. As a result, the peer review process became tougher. Then, there appeared a widespread perception in the community that publishing in Cell is a great achievement. As a result, not only “what to publish” but also “which journal to publish” became very important, and the journal ranking began to have authority.

The “Impact Factor” has accelerated this trend. Simply put, the Impact Factor measures the average number of times an article published in a journal has been recently cited. People used this measure to evaluate how a journal has an impact. Then, journals with a high Impact Factor were considered highly ranked journals. As a result, the ranking of journals became quantified, and the authority of journal ranking became firmly established.

This authoritarianization made it important for researchers to publish their work in highly ranked journals. This ranking was actually used to evaluate other researchers and their employment as researchers. This effectively eliminated the idea of abandoning journals as a place to publish one’s work. I believe this is one of the reasons that made it difficult to solve the problem of academic journal publishing.

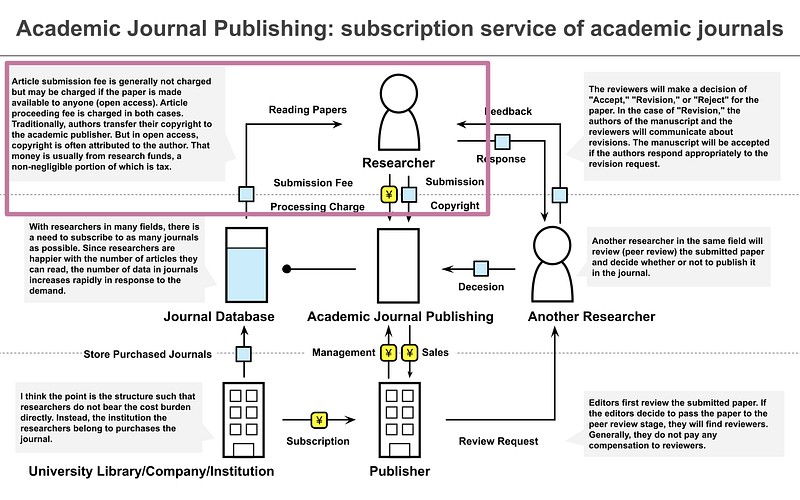

Structure of separation of beneficiaries and cost bearers

The second reason is the structure of separation of cost bearers and beneficiaries.

First, the beneficiaries are the researchers. Since there is no reason not to have more journals, researchers have the motivation to buy as many as possible if they can do so without hindrance.

Next, the cost-bearers are the research institution (in the case of a university, the University Library). Research institution contracts for journal subscriptions directly from academic journal publishers. Since researchers know best what they need and how much they need, university libraries are willing to respond to requests from researchers as much as possible within their budget.

Since the cost bearers and beneficiaries are separated, researchers are not likely to request a reduction in the number of journals purchased. And university libraries try to continue journal subscriptions for researchers as much as possible. I believe this is one of the reasons for the currently unsolved problem of academic publishing.

The beneficiaries and cost bearers are separated for other expenses as well. Researchers rarely pay for research-related expenses out of their own pocket. When a researcher pays an article submission or proceeding fee, these costs are funded out of the research budget. And not a small percentage of research expenses are public funds, i.e., taxes. I believe this reinforces the structure of commercial publishing’s exploitation from the research industry. Dr. Arita wrote about this to be very accurate, and I quote it below. Note that this is the case in Japan and is not necessarily the case in other countries.

The problem with commercialization is that participation fees for conferences and submission fees for journals are covered by public funds (taxpayers’ money to begin with). Few researchers pay conference registration fees or journal submission fees out of their own salaries. And as far as public funds are concerned, researchers seem to be price insensitive: how many researchers would pay more than 100,000 yen (700 dollars) for participation fees or 1,250,000 yen (about 9000 dollars) for open access to Nature, even if they had to pay the fees themselves? … commercial publishers are well aware of this situation and set their prices accordingly.

Tuition and public funds are important for many universities’ revenue. Therefore, I think it is the taxpayers and students are more directly affected by these exploitative structures.

However, the vast majority of students graduate from university without having made research their profession. And the majority of taxpayers have no way of knowing what is going on in the research industry. Thus, the cost payers have little or no voice in the matter. I suspect that this separation between cost-bearers and beneficiaries supports the exploitative business of commercial publishing.

Importance of considering systems that allow maximization of individual utility to optimize the overall objective

I have shown how academic journal publishing has formed an exploitative structure. I have also explained that the current research ecosystem supports this structure. But what I want to discuss here is not who is to blame. What I want to discuss is the structure behind the problem.

While I believe it matters to clarify where the problem lies, I do not think it is constructive to look for the attribution of blame. Maxwell started this business model and Elsevier expanded it because they made the best business choice under the conditions of the research industry. Maxwell did provide solutions to the needs of the scientists of the time.

The same holds for researchers. For example. in Japan, it was difficult for researchers to carry their awarded budgets to the next year until recently. It was even common for the next budget to be reduced (explicitly or not) for over-request if the pledged budget was not fully used.

It is natural, then, to think that the budget must be used up in any way possible. It is understandable that the idea of “the more money we can spend, the better” would rather arise. The system design discouraged researchers from saving money.

You also cannot ignore the reality that the job market for researchers remains difficult. Even if the problem is increasing the number of papers, the only way to survive as a researcher is to publish papers and aim for top journals. In an environment where one’s own survival is threatened, it is harder to be a good person. I believe that pressuring individuals to change their behavior will only make the situation worse, but will not solve it.

It is natural for humans to optimize their benefit in a given environment, and I think that should be. What needs to be changed are the rules, the game, and the structure behind it. What we should think about is not “who is at fault,” but “what is the problem” and “what kind of game should be designed to solve it”.

I believe that a system that imposes burdens on people will eventually break down and fail. Above all, I have a sense of value that the people in the system will not be happy. I believe it matters to consider how to design a system in which each individual maximizes their own utility, but is optimal for human knowledge development.

Importance of history in considering systems that solve problems

In considering a system to solve the challenges of academic publishing, I believe it matters to start by determining the target state of what research should be like. Then, the current system should be considered relative to the multiple possible systems. We should consider ways to bridge the gap between the current system and the target state.

Knowing history helps us to relativize the present. For example, in the research industry, we often hear the phrase “publish or perish” (publish your paper or stop being a researcher). However, as mentioned above, publication in academic journals has not been as essential as it is now since the 1960s. It was not until the 1970s that everyone started aiming for the top journals and the impact factor became important. I didn’t explain it this time, but even peer review has become so important since the 1970s.

The Rise of Peer Review: Melinda Baldwin on the History of Refereeing at Scientific Journals and…In this interview Robert Harington ask Melinda to talk about her recent article in Isis, entitled Scientific Autonomy…scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org

We assume all of these practices are essential to research. However, they all began only five or six decades ago. Consider that Einstein published his theory of relativity in 1915, Newton published his laws of motion in 1687, and Euclidean geometry was born around 300 B.C. Then, you can see how recent 5 or 60 years ago is in the history of research.

Also, while the current system may have been optimal at the time it was created, everything is different now than it was in the past. The Internet is commonplace now. Governments do not invest in science and technology as much as they used to win the immediate war. And the number of researchers and publications is not comparable.

Given this, it is only natural that the current research system is falling apart. I think the discussion about what research is and should be, and what should be done to achieve it from scratch is crucial.

Recent trends in academic journal publishing

The problem of exploitative business models by major commercial publishers has been frequently pointed out. In recent years, efforts to eliminate these problems have begun to accelerate.

A prime example is “Plan S,” promoted by Europe. The plan is to require that research funded by 11 European institutions be made open access from January 2021 (planned for January 2020 at first). Although there are many issues to be addressed, I believe this is a very significant attempt to change the business model of commercial publishing.

HomeAbout Plan S Plan S is an initiative for Open Access publishing that was launched in September 2018. The plan is…www.coalition-s.org

The U.S. government has also announced its policy of requiring immediate open access to the results of government-funded research from 2025 onward. This is very significant that such a move was followed in the United States, the world’s largest research nation.

The shift to open access for papers and the business model of commercial publishing will continue. I will monitor these trends closely as I consider the future of research.

Conclusion

In this article, I discussed what academic journal publishing is, what problem it has, when it started, and why it continues.

I believe the discussion about how to solve the problem rather than blame something is indispensable. I’m going to contribute to resolution of these issues as well, as I promote the automation of research and explore various ways of doing research. I wholeheartedly support those engaged in these activities and welcome those who work with me to promote these activities. Let’s move forward together toward a better way of doing research!