"The AI Scientist" and some metascientific considerations

AI can now write research papers. What does that mean for science?

Summary: This year Sakana AI unveiled "The AI Scientist," a system that can automate the whole process of machine learning research, from generating ideas to writing papers. Shiro, an independent ML researcher who works on research automation, and Ryuichi, an independent editor have been continually discussing the transformative impact of AI on the scientific ecosystem. This essay is a preliminary reflection on the transformative potential of "The AI Scientist", the technical hurdles in research automation, and the broader questions facing us: How should we approach this scientific transformation, and what conversations must we have along the way?

Note: This article is an English adaptation of the draft version of a Japanese article originally published in Nikkei-Science in December 2024. We thank the publisher for granting us permission to translate and publish this material.

§1 The impact of "the AI Scientist"

In August 2024, Sakana AI, a Tokyo-based AI startup, released "The AI Scientist," a system that can automatically execute the whole process of machine learning research, from generating research ideas to peer review. Founded by prominent former Google researchers, Sakana AI has been attracting attention for its approach to AI development that differs from simply scaling up models. The AI Scientist has been met with surprise in the scientific community.

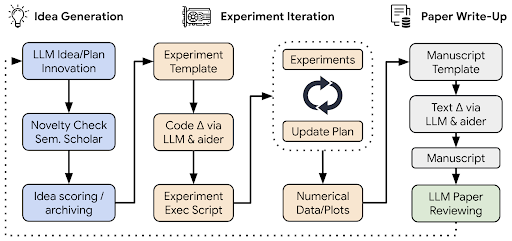

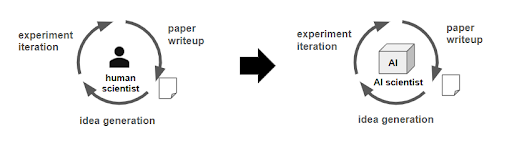

The AI Scientist is composed of combined Large Language Models (LLMs). Based on initial ideas provided by humans, it can generate machine learning research concepts within a computer, selecting those with novelty. It independently modifies pre-prepared Python code templates, implements and debugs code, and improves experimental plans as needed. Using the obtained experimental results, it visualizes data through graphs and then writes and outputs a paper as a PDF. Moreover, it conducts a peer review of the paper using LLMs and provides feedback for future improvement.

(Credit: Sakana AI https://sakana.ai/ai-scientist/)

The preprint published alongside the system's source code includes examples of ~10 page-long papers generated by the AI Scientist. These examples demonstrate not only the ability to generate appropriate abstracts and introductions but also to formalize methods using mathematical equations and even generate original figures not present in the provided templates. While there have been previous attempts to automatically analyze data and generate reports, this is the first successful attempt to let AI conduct research at a level indistinguishable from human work and automatically write an academic paper. The authors evaluate this system as being at the level of "an early-stage ML researcher who can competently execute an idea but may not have the full background knowledge to fully interpret the reasons behind an algorithm's success."

§2 A short history of the intersection of science and AI

AI's potential applications in science have been explored for quite some time. The earliest attempts date back to the 1950s and 1960s.

DENDRAL in the 60s aimed to automatically discover unknown organic compounds by mimicking the decision-making processes of organic chemists. BACON in the 70s was a system capable of automatically discovering empirical laws from data. By the 2000s, classical artificial intelligence combined with robotics led to the creation of Robot Scientists like Adam and Eve, which could generate hypotheses and execute scientific experiments automatically. The Nobel Turing Challenge proposed by Hiroaki Kitano (the current CEO of Sony AI) around 2016 can also be considered an attempt to realize AI-as-a-scientist. These early research efforts were ambitious, attempting to automate experiments including those in the real world.

The application of machine learning to scientific discoveries began to increase in the late 20th century. Research flourished in various areas: using machine learning to discover mathematical formulas describing laws behind scientific observational data, attempts to make new scientific discoveries based on existing papers, and applying Bayesian optimization to explore experimental design. In the 2000s, data-driven scientific research such as Materials Informatics and Bioinformatics flourished.

With the rise of deep learning, AI applications in science increased dramatically in the 2010s. Applications advanced across various fields including materials science, biology, and medicine. As exemplified by AlphaFold, AI began to solve important scientific challenges that humans had been unable to solve. Beyond applied research, fundamental machine learning research for handling scientific data made significant progress in research areas such as Physics-Informed ML (machine learning incorporating physical laws and prior physics knowledge), SciML (fusion of traditional scientific computing and machine learning), and Geometric Deep Learning (deep learning focused on geometric data structures). These attempts have recently come to be collectively termed "AI for Science." The 2024 Nobel Prizes demonstrated the widely recognized impact of AI on science.

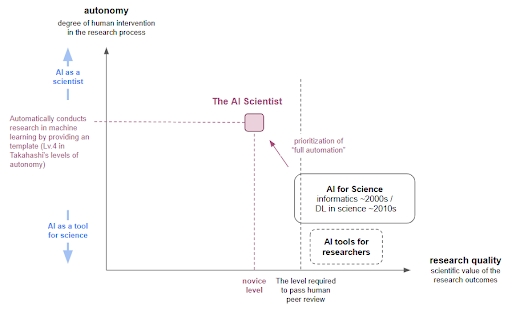

These efforts can be categorized based on their motivations: whether they aim to create "AI as a tool for science" or "AI-as-a-scientist." While the former aims to develop AI that can effectively solve specific scientific challenges and tasks, the latter explores "what it means for AI itself to do science" and aims to create AI capable of conducting science. In the former case, it's sufficient to have AI specialized for solving specific problems, with humans deciding what should be solved. This requires a high capability to solve real scientific problems. On the other hand, the latter aims to create AI that can think for itself and execute all research processes like human researchers.

| Level of autonomy | Details | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Level 0: Computation | Computations performed based on programming. No autonomy is exhibited. | Data processing, classification, and simulations performed by computers following programmer instructions. |

| Level 1: Solution Search in Closed Systems | Search for solutions based on given search space and objective functions. Search is closed within the computer. | Move search in Go, medication planning based on expert systems, etc. |

| Level 2: Search in Open Systems | Solution search in open systems where evaluation is obtained only after experiments. AI plans which areas to explore. | Exploration of cell culture conditions. Search for photocatalysts using experimental robots and Bayesian optimization. |

| Level 3: Fixed-Form Hypothesis Generation | AI searches for hypotheses within human-provided formats and generates experimental plans to verify them. | AI robot systems that plan and execute experiments while improving models with fixed formats. Discovery of physical laws from experimental data. |

| Level 4: Free-Form Hypothesis Generation | AI explores and discovers the format of hypotheses and models itself (e.g., the discovery of Neptune). May require new observational quantities or equipment for verification. | Sakana AI's AI Scientist has achieved Level 4 in limited domains. |

| Level 5: Research Planning | Humans only provide research objectives to AI, and AI develops research plans independently. | Not yet achieved. |

| Level 6: Research Objective Setting | AI sets its own research objectives, finds suitable research subjects, and conducts research. | Not yet achieved. |

§3 Technical challenges of AI-as-a-scientist

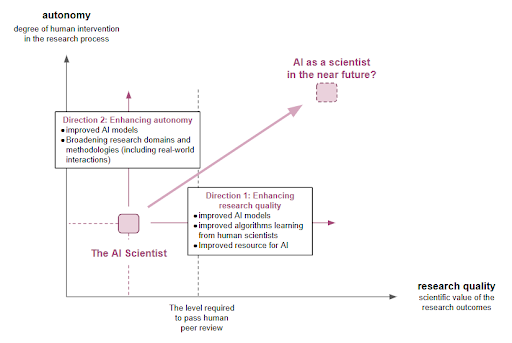

Despite the progress, numerous challenges remain in realizing AI as a scientist. First, there are issues with the quality of generated research. While the current technology occasionally produces interesting ideas, it cannot yet generate truly groundbreaking concepts that could lead to the next scientific innovation. The generated papers are not yet at a level that would be accepted by top-tier academic publications or international conferences. There are many areas for improvement, including idea implementation, experimental code, data usage, analysis of prior research, and the overall discussion structure of papers.

Even if high-quality research could be executed, it would not yet be considered AI-as-a-scientist due to insufficient autonomy. While the novelty of Sakana AI's AI Scientist lies in its high autonomy, the fundamental experimental code, initial ideas, research tasks, and research domains are still determined by humans. More precisely, current technology requires humans to design the research execution procedure and determine what should be done at each step. In essence, it is merely automatically executing a predefined typical research workflow.

A truly "scientific AI" would be expected to:

- Think independently

- Develop long-term plans

- Set goals

- Construct research workflows

- Make adaptive decisions and execute research

As repeatedly mentioned, the AI Scientist is limited to executing certain machine learning research within digital space. However, many natural science research fields require collecting data through experiments and observations in the physical world. To automatically execute such research from goal setting and idea generation stages, many technological challenges remain.

In fact, efforts to address these challenges have already begun:

- A research group proposed a method in October 2024 to generate more highly evaluated research ideas by explicitly incorporating information about human research processes.

- Another group proposed a framework where a "CycleReseacher" and a "Cycle Reviewer" iteratively learn, mimicking actual research-review-modification cycles.

- In Japan, the AutoRes project led by Wataru Kumagai at OMRON SINIC X is exploring methods to automatically combine two ideas to generate new concepts.

Through such research, AI-as-a-scientist is expected to progress in both research quality and autonomy. However, whether AI can do science depends on the definition of science/ research. As we'll see later, AI might potentially change the very meaning of research. Therefore, these technical challenges should be understood as being premised on current science/research.

§4 How will AI-as-a-scientist be used?

The scientific community's immediate concern is how AI-as-a-scientist like the AI Scientist will actually be integrated into scientific practice.

Even if an AI becomes capable of generating ideas and writing papers in a specific scientific field, it's unlikely that "AI-written papers" would be immediately accepted. Research reliability would be a key issue. Two months after ChatGPT's release, Science magazine's editor-in-chief Holden Thorp published an article titled "ChatGPT is fun, but not an author", and the journal initially declared it would not accept papers containing AI-generated text or images (though this ban was later slightly relaxed). To varying degrees, Nature and other publishers, research funding agencies, and academic conferences have maintained that AI should be a tool, and humans should be the writers.

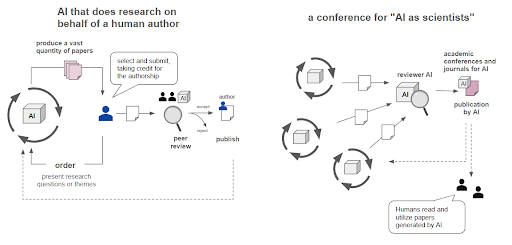

A more realistic approach is likely to be "AI does research on behalf of a human author". Humans would select promising papers generated by AI, and carefully review and modify them before submission. If human authors maintain responsibility, the use of "research and paper-writing AI" might gradually become accepted. In this scenario, scientists' roles would shift from research executors to supervisors who provide instructions to AI and select promising results.

This role transformation is already underway. A recent MIT study found that researchers using AI tools in materials development now spend more time on the "judgment" of results than "idea generations." (Updated May 17, 2025: MIT has announced strong doubts regarding the validity of this research. See: https://economics.mit.edu/news/assuring-accurate-research-record) As more research processes become AI-replaceable, human scientists will increasingly supervise these loops and take responsibility.

§5 Metascience anticipates the future of science

As suggested by the idea of an "AI-AI conference", science is not just individual researchers' work but a kind of social game. While science's ultimate goal might be some objective truth, its practice is a collective human endeavor that changes over time.

For example, the practice of peer review among researchers became established in the 1970s, whereas previously journal editors primarily conducted reviews. When Eugene Garfield, a pioneer in research metrics, made paper citations visible, paper value began to be measured by citation count. Recently, recognizing the problems of citation-centric research evaluation, alternative impact measurements (altmetrics) and qualitative assessments have gained importance.

The "metascience" perspective attempts to capture what kind of social game science represents. Broadly encompassing science history, philosophy, and sociology, metascience has recently evolved into a movement focused on actively improving science. If AI might change the very game of science, the metascience perspective becomes crucial.

For instance, Professor Jun Otsuka of Kyoto University, a philosophy of statistics expert, has considered AI's impact on the justification of scientific knowledge. Traditional science used human-comprehensible statistical methods like hypothesis testing to conduct objective, rational inductive reasoning. However, deep learning can predict and control subjects without human understanding. This suggests the possibility of justification without human involvement, potentially fundamentally challenging modern science's assumptions about rational and objective knowledge generation.

These discussions are just beginning. In 2021, an OECD working group held a workshop on "AI and Scientific Productivity". In Japan, researchers like Makoto Kureha and Minao Kukita have long examined AI's potential long-term impacts on scientific creativity and understanding.

Below are some of the metascientific questions on AI in science that are beginning to be discussed:

- Questions from a researcher's perspective

- What parts of research can AI assist with?

- Questions from the philosophy of science

- How will the "justification" of scientific knowledge change in the age of AI?

- Is there a justification that cannot be understood?

- Can an AI that conducts research become a subject of "understanding"?

- What does it mean for AI to understand?

- In the age of AI science, will "understanding" continue to be the purpose of science?

- What happens to understanding when prediction and control are possible without understanding?

- Can AI make creative scientific discoveries?

- What is creativity in the first place?

- How will the "justification" of scientific knowledge change in the age of AI?

- Questions about the social process of science

- How can AI streamline scientific discovery?

- Can AI conduct peer review?

- Can AI be used for researcher evaluation and grant review?

- How can AI be used for science communication?

- Can AI help detect and prevent research misconduct?

- How will AI change citizen science?

- Questions about the risks of AI

- How can AI be used for research misconduct?

- To what extent can scientific AI be used for dual use and crime? (e.g., discovery of dangerous drugs by AI)

- Will AI increase low-quality research?

- Will AI reinforce biases toward specific languages and cultures in science?

- How will AI affect the well-being of scientists?

§6 What happens after this?

This article has examined how Sakana AI's "The AI Scientist" prototype has brought the vision of AI-as-a-scientist closer to reality by demonstrating a comprehensive research workflow system. We've seen that future AI model improvements could enhance research quality and autonomy.

From a metascience perspective focusing on science as a social process, however, it becomes clear that a perfect "paper-writing AI" is not the ultimate form of AI-as-a-scientist. The very nature of academic communication might change through AI.

Recently, scientific policy has increasingly been demanding open data: making all research data and source code publicly available. Since AI-conducted research potentially involves hallucinations, objective methods of evaluating result validity will be even more crucial. Scientific AI might accelerate the transition to academic communication that doesn't center on papers.

What might next-generation science look like when academic knowledge is no longer necessarily tied to papers? One may envision a world where scientific achievements are registered in foundational models. We can also easily imagine a future where "AI for Science" results are proprietary and enclosed within private companies.

The positioning of AI offers various possibilities. Is scientific AI an "assistant", a "colleague", a "rival", or an "infrastructure" for human scientists? Regardless of what the future brings, we are undoubtedly in a period of scientific transformation. While significant risks exist of undermining scientific values and norms, this is also an opportunity to improve longstanding scientific problems. Thus we would like to everyone ask themselves: "What kind of science do we want?"

A group led by Tadahiro Taniguchi at Kyoto University (in which Shiro is a member) has begun the attempt to mathematically model science as a collective cognitive process. Such metascientific modeling attempts may help our conversation and active shaping of the science of tomorrow.

Now that AI can write research papers, it's time that all of us engage in a discussion on how we would like AI to change science.